Well... is it actually better? And if it is better, when is it better, for whom and why?

I understand how useful mapping information is for big picture decision making, trend spotting and knowledge sharing at different levels. Mapping in various forms is incredibly useful for program and advocacy work, and there are many examples of how crowd sourcing, digital mapping, and information geo-visualization can be done successfully (mapping stockouts, elections monitoring, human rights incident reporting, crisis management, public health). The potential is huge and exciting.

But when I’m sitting around with a group of people in a rural community without many services, it can be pretty hard to remember or to explain the benefits of digital mapping over low tech map making. Why should people make a digital map if they only have sporadic electricity and internet access (if at all) and not many smart phones. How will they access that digital map on a regular basis once they make it? Does the fact that they could make a digital map, necessarily mean that they should?

I guess my key concern is around how digital mapping is directly useful for the folks who are inputting the information, building the map. The "what's in it for them" question.

As I was pondering this nagging question, @NiJeL_mapping posted something on Twitter that caught my eye and helped spur along the idea of working through these thoughts. He was at the Mobile Data for Social Action in the MidEast conference, hosted by UNICEF Innovations and MobileActive. He tweeted: "what data are we going to collect, how will we collect it, and from whom?" Then he tweeted: "Again, the push for technology w/o any knowledge of the intended outcome is frustrating" And a last tweet "overhearing whispers about how we need to focus on the technology, but impossible w/o knowing info to collect". This really reminded me that you need to have clear objectives and reasons for collecting data before you decide what cool new technology will be used to do it. A few days ago I read JD's blog post giving an overview of the whole conference. The key point for me was that the 'target' population delegation "felt overwhelmed by the host of tools and projects presented to them and were unsure how any of this could benefit them". Luckily, he said, the conference organizers realized this and quickly altered the course of the event.

--------------------

Well, if you have ever asked yourself a question, it's pretty likely that someone else has asked it too, and you can find some answers online. So I went digging around for thoughts from 4 initiatives that I've been following over the past year or so: Ushahidi, MapKibera, Wikimapa, and now NiJeL too.

In very quick summary, Ushahidi is often (but not exclusively) used as a crisis mapping tool for rapid crowd sourced information, decision making, and trend analysis. Map Kibera and Wikimapa both use mapping and user-generated media for social inclusion, community voice, community media and community planning. NiJeL works with participatory mapping, bringing it to the web for a variety of geo-visualization uses such as planning, resource allocation, impact visualization and advocacy.

Mine must be not be a unique query, because I found that Erica from Map Kibera answered it pretty directly a couple weeks ago in a blog post called Maps and the Media "...the question about benefit to those who aren’t online misses the point. The digital divide is a fact and needs to be addressed, but when it comes to community information there is also a need for expression outward and collaboration within Kibera. Something like the Kibera Journal or Pamoja FM allows Kibera to talk to itself, while putting facts and stories online allows it to speak to the rest of the world (including wired Nairobi, politicians, national press)."

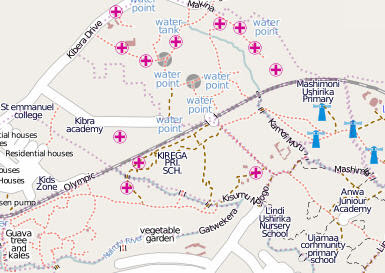

The objectives of Map Kibera seem similar to those of the YETAM project, the initiative that has taken up most of my work hours over the past couple years. YETAM's main goals are engaging youth in the local development process and helping them develop the skills and tools to communicate and advocate for their rights and their ideas with local, national and global audiences. The project starts off with map making to visualize community profile, community history, community resources, and risks to child rights and protection. Group discussions ensue, issues are prioritized by the youth, and they then create art and media around those issues. The arts and media materials that youth produce throughout the project are shared with community members, district officials and national authorities to generate dialogue. They're also plotted onto a digital version of their map and uploaded to the web for the global audience.

Since the local audience is the main one for the media and arts that youth produce during YETAM project activities, followed by district, national and global audiences, it would seem then that the same is true for the map. It must first speak to the local audience, to the community. It should be first useful to users and producers of the information, as a learning/discussion tool and as a decision making tool, and secondly be useful to a national and then a global audience. Perhaps this will be the case for many of the initiatives that Plan supports and facilitates, given Plan's child-centered community develop approach and the fact that we use participatory mapping methodologies in our community work all the time. So we need to find a way for the hand-drawn map to be transformed into a digital map (this is what we've been doing up to now in the YETAM project), or find a way to make a digital map attractive and useful to local people. Or we could also keep doing both the low-tech and the digital versions.

[Update: "Paper rocks!" Mikel from Map Kibera (read his comment below) shared some additional tools that Map Kibera uses to ensure that information collected is available in the community. One is called Walking Papers. It is a paper based GPS where you print the map, re-draw it or add details, scan the new version and it automatically geo-rectifies the paper. They will also be printing and distributing paper maps, and considering forums around the paper maps to increase participation from people who don't use computers. Also Mikel commented that drawn maps like the one in the image above can be stored and/or made available to the community using Map Warper. Here you scan and upload a map, set control points, and then get a geo-rectified version for use online. Excellent. This gets better all the time. :-)]

The Wikimapa Brazil project (paraphrasing from their website) aims to promote social inclusion using virtual and mobile mapping in low-income areas and slums, since available mapping services have not offered information from these marginalized areas. The project aims to democratize access to information and raise low-income youth's social participation from simple consumers of information to providers of information and change agents promoting local development and broadening perspectives and creating new cultural and geographical reference points. In this case, the project goals are similar to YETAM and Map Kibera, but the project is primarily aimed at reducing marginalization and exclusion within available mapping services. Therefore it seems relevant that on-line mapping is chosen as the mapping methodology. It may also be the case that residents in the project area have easy access to internet, meaning they would be able to continually use and benefit from the on-line maps.

Patrick Meier from Ushahidi and the Harvard Humanitarian Institute talks specifically about the concepts of participatory mapping, social mapping and crowd feeding during this 30 min video. He comments that the information that's collected via "crowd sourcing" needs to go right back to ‘the crowd’ who provided it (crowd feeding). One way that Ushahidi is doing this in communities that do not have regular access to internet is by allowing people to subscribe to SMS alerts when a crisis event hits a particular area where they have a special interest. Another way to ensure that map makers have information returned to them, he says, is to use transparencies in a manual approach to GIS where information is made more compelling by laying thematic transparent layers over a base map to show dynamic changes and trends.

Patrick points to Tactical Technology Collective's Maps for Advocacy booklet which documents a number of different mapping techniques and mapping projects and how they have been used for advocacy. So, I would conclude that in the case of Ushahidi and crisis mapping to see trends in time and space, to have immediate and up to date information, and to manage a broad set of information for crisis decision making, it also is logical that an online map is the primary mapping methodology. In this case, the information is crowd sourced, so it comes from many, and it's processed and aggregated on Ushahidi to go back to many. Because the information in a crisis situation is changing rapidly, it would be difficult to use a static map, a hand drawn map or one that is updated less frequently.

In the case of Plan, as part of the Violence Against Children (VAC) project we are planning to pilot incident reporting by SMS of violence against children and subsequent mapping of the situation in order to raise awareness among families and community members, and to advocate to local, national and global authorities to uphold their responsibilities and promises in this aspect. The question here will be how to make both crowd sourcing and crowd feeding something that is easily accessible by the participating youth and communities as well as to the other audiences in order to have the desired impact and reach the desired outcomes. The participating youth have already been trained on violence against children (VAC), its causes and effects, and ways to advocate around it. Now the key will be training them on the technology so that they can discover and design ways to use it to meet their goals. A key point will be evaluating whether the outcome is a reduction in VAC.

So in conclusion I would have to say that one map is not better than the other map. They are both amazing tools and need to be selected depending on the situation. There is no one size fits all. It goes back to the point of having defined objectives and outcomes for the initiative, knowing what information will be collected, why, with whom, by whom, and for whom first, analyzing the local context as part of that process, knowing about what tools exist and finding the right tool/technology/information management process for the goals that people want to reach based on the context. It's also about keeping the end-user in mind, and ensuring that those who are producing information have access to that information. I think I will have to keep my question in mind at all times, actually.